Faculty members say they’re increasingly feeling burned out, in part due to the prevalence of technology in and outside of the classroom.

ajijchan/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Almost half of faculty members nationally feel burned out because of their work—and a similar number (39 percent) felt emotionally exhausted, according to a report released Thursday by the College Innovation Network.

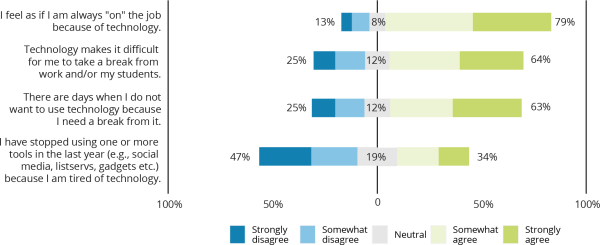

While burnout among professors is nothing new, Omid Fotuhi, director of learning and innovation at WGU Labs—a subset of Western Governors University that funds the College Innovation Network—believes technology could be greatly contributing to it. According to the report, roughly eight in 10 faculty members feel that they’re always “on the job” because of technology, while another 64 percent say technology makes it difficult to take breaks from students or work.

“Faculty now see technology as not only a permanent but also a growing influence on learning,” write the report’s authors, noting that that viewpoint can create a divide among professors who want technology in the classroom and those who do not. “Such growing chasms among faculty may pose challenges, inefficiencies, and inconsistencies in teaching and instruction, which administrators must navigate.”

Many professors feel like they constantly have to be available, leading to burnout, according to a new report.

This is CIN’s fourth annual report focused on faculty. The network, a consortium that supports higher ed institutions as they navigate emerging technology, also releases annual reports on administrators’ and students’ thoughts on tech and innovation in the classroom.

“We’ve been tracking perceptions, beliefs, behaviors and anticipating investment in education from faculty, students and administration, with the intention to connect the dots,” Fotuhi said. “There were a lot of questions we couldn’t answer by talking to just one group.”

The faculty report surveyed 359 faculty members in November 2023, spanning community colleges, online-only colleges and brick-and-mortar, four-year institutions.

The intersection of the reports over the years has allowed Fotuhi to delve further into the latest findings. He said he has always been struck by faculty members’ ambivalence toward artificial intelligence, with many using the tools but retaining skepticism about its efficacy. According to the report, more than half (53 percent) of instructors believe AI will enhance the student experience—although a similar percentage are not using it in their classrooms. That lines up with other reports that find students’ AI usage far outpaces faculty use.

The skepticism may derive partly from how ed-tech decisions are being made. According to the latest report, 87 percent of faculty members said their administrative team makes decisions on ed-tech implementation and usage. Fewer than 20 percent reported that their institutions sought their feedback on ed tech once a year or more frequently, and about the same percentage said their institutions involve students in the process.

“That’s where we got to the root cause: Faculty don’t feel they’re involved in the decision-making process,” Fotuhi said. “They don’t think their input is valued, which fuels the idea about [technology’s] effectiveness.”

Whether faculty members believe higher education is heading in the right direction often corresponds with the types of courses they teach, according to a new report.

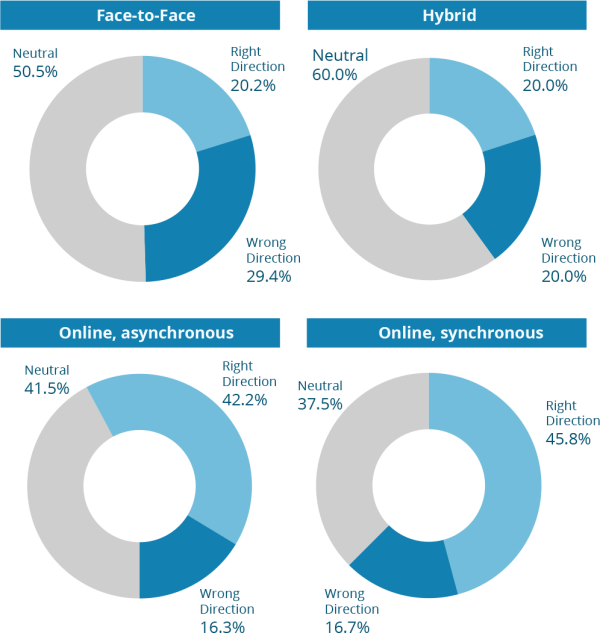

Those feelings about technology’s effectiveness play into faculty members’ thoughts about the direction of higher ed over all. They acknowledge reality: According to the report, almost all faculty members (92 percent) believe they will use more ed-tech tools, like AI, in the future. The vast majority (86 percent) also expect to spend more time delivering course content online. But 20 percent believe higher education is heading in the wrong direction because of its focus on technology in the classroom, with just 32 percent believing it’s going in the right direction.

More worryingly, one-third (37 percent) of faculty members said that students will have lower-quality learning experiences in the future because of the increasing use of technology. A similar percentage believe that the value of higher education will decline going forward.

Perhaps not surprisingly, that outlook shifts a bit when accounting for the type of instructors being surveyed: Roughly 40 percent of those who teach online believe that higher education is headed in the right direction, in part because of its increased technology usage, while just 20 percent of professors teaching in-person courses state the same.

Despite the difference in future outlooks, more professors are taking a positive view toward course modalities than in past reports. Seventy-nine percent of faculty members said they feel positive about offering more modality and credential options to students, while 76 percent feel positive about offering more hybrid courses (mixing remote and in-person instruction) for students. By contrast, the 2023 report found just over half of faculty felt positively about institutions offering increasing numbers of online courses and programs.

Fotuhi suggests institutions do two things in order to combat the rising tensions surrounding technology and burnout. First, when an institution is making potential technology investments, it should offer feedback channels for feedback from professors and students to voice their opinions. And then, when those investments are made, it should offer support and guidelines to implement the new infrastructure or technology.

He acknowledges that it is easier said than done.

“Most administrators, they’re just fighting to stay afloat; it’s a really difficult time for higher education,” he said. “Administrators are making decisions on the limited information they have; that affects faculty on support and job satisfaction, which impacts students. It’s a systems issue, so we’re trying to connect the dots.”